Guarani AI: When building language tech means building community

El Surti’s AI initiative is building more inclusive technology through chatbot training and voice data collection. Learn how the local communities are leading the way

First gathering of Pytyvohara (community facilitators) cohort at El Surti's newsroom in Asunción (Credit: Milena Coral).

By Alejandro Valdez Sanabria & Sebastian Auyanet

In early May, something quietly powerful happened in Asunción, Paraguay. It wasn’t just the official kick-off of our dataset mingas (a collective work gathering where communities come together to build something for the common good) for populating Mozilla’s Common Voice dataset. It wasn’t even the moment our AI chatbot finally began handling real subscription requests. It was something deeper — a turning point in how we’re reimagining the intersection of language, technology, sustainability, and community for our organisation.

The project: AIkuaa

AIkuaa (a pun combining “AI” and the Guaraní word “ikuaa”, meaning “to know” — roughly, “I know AI”) is an initiative led by El Surti to create and strengthen open voice data in Guaraní, one of Paraguay’s official languages and among the most widely spoken Indigenous languages in South America.

Large language models (LLMs) have deepened the digital divide, as predominantly oral languages such as Guaraní are severely underrepresented due to the lack of training data. This has left nearly seven million speakers across Paraguay, Bolivia, and Argentina even more vulnerable to disinformation, digital exclusion and the erosion of their linguist rights.

First gathering of Pytyvohara (community facilitators) cohort at El Surti's newsroom in Asunción

Our goal is simple but ambitious: to ensure that voice technologies — from speech recognition to AI assistants — can understand and speak Guaraní.

How are we doing this?

Organising mingas (community-led hackathons rooted in Latin American traditions of collective work) to populate Mozilla’s Common Voice dataset with Guaraní audios.

Training AI models to understand spoken Guaraní, using the contributions collected through the mingas.

Integrating with a chatbot capable of processing spoken Guaraní to engage with our community in their own language.

Building an open knowledge repository to enable organisations and media outlets to better serve oral-language audiences.

Ultimately, this is about designing cultural infrastructure — so people don’t just contribute to AI, they shape it at a systemic level. In this short blogpost, we’re sharing a few insights from what we’ve learned so far.

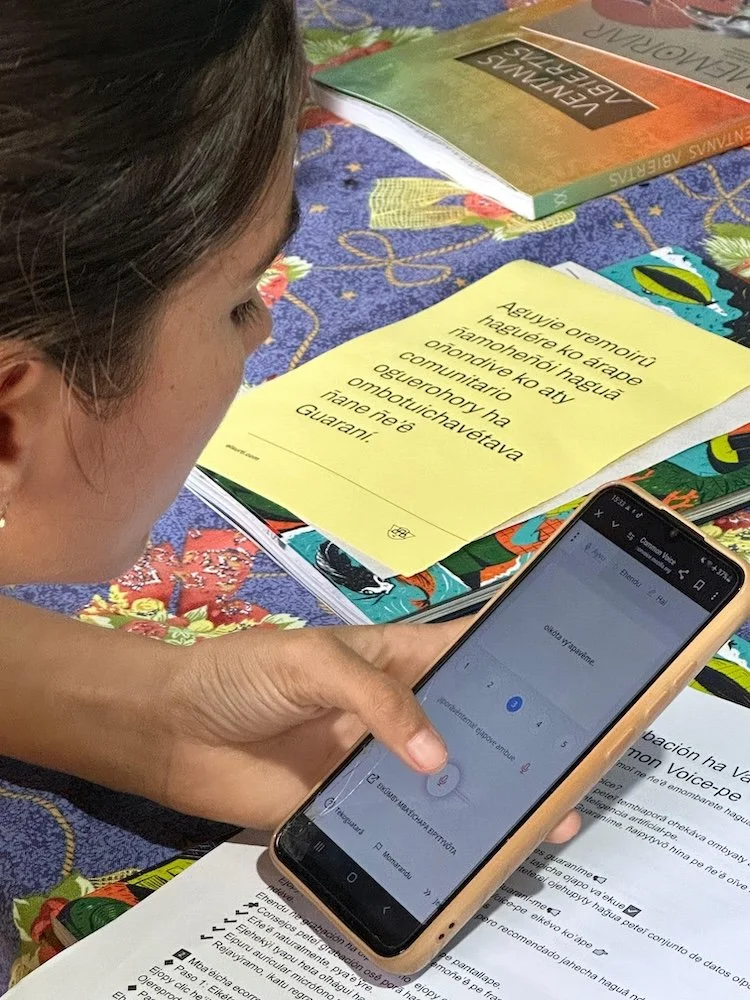

Guarani audio population with the Common Voice interface at a minga in Arroyito, 320km away from Asunción, Paraguay.

Creating a community of open voices: A milestone of belonging

One of our first milestones was about more than just meeting a deliverable — it was about energy, coordination, and, above all, a sense of belonging.

On May 11th, we hosted our first in-person gathering — a minga — with the amazing cohort of Pytyvõhára, the facilitators trained to lead our community hackathons. They will be at the heart of a growing network for open voice data in Guaraní — a true community of open voices. The results were moving.

Our guides worked (with room to iterate), our vibe was collaborative, and participants weren’t just eager to contribute — they genuinely felt part of something meaningful.

One of the most revealing insights? We realised that the best way to scale this effort isn’t just digital — it’s hybrid. We learned that contributing to a voice dataset can be slow, tedious, and even feel extractive. But when we turn a solitary task into a collective act of participation, it becomes a powerful call to civic action.

Print materials for audio population with El Surti's print magazine as a gift in a minga in Arroyito.

Learning by doing: Designing for an oral language

As always, prepping for the first hackathon took time. We needed the right facilitators, the right workflows, and a method that didn’t just “work”, but honored the cultural significance of what we’re trying to build. Designing the onboarding, the tools, and the guidance so that contributors felt empowered — not just instructed — was a process of learning in itself.

After our first gathering with our pytyvõhára cohort, we sent them out with specific guides to implement their own local mingas.

At a technical level, these mingas play a crucial role: ensuring that the voice dataset is robust and truly representative. That means collecting diverse samples in terms of accents, tones, ages, speaking speeds, and volume levels. By creating spaces where people from different regions, generations, and speaking styles participate, the activity helps capture the richness and variety of Guaraní as it is spoken in real life.

One of the key lessons we’ve learned: the benefits of contributing to open voice data are often indirect and long-term. That’s why, beyond fostering a sense of belonging, we’re learning to embrace the cosmovisión embedded in the language — and to offer meaningful learning opportunities that can motivate and sustain participation.

This focus on cosmovisión matters deeply. Because a language is never just a set of signs — it’s a worldview, a way of understanding time, relationships, and life itself. And that worldview doesn’t always align with colonial languages like Spanish, English, or French.

Another major challenge we’ve encountered is that, even in projects like Mozilla’s Common Voice, the user experience (UX) is still designed with written-language traditions in mind. Yet many Guaraní speakers don’t necessarily express themselves through writing. For now, we’re developing a mixed methodology within our mingas to bridge that gap. But we’re also actively exploring alternatives to standard UX/UI design — ones that give form and space to oral languages like Guaraní.

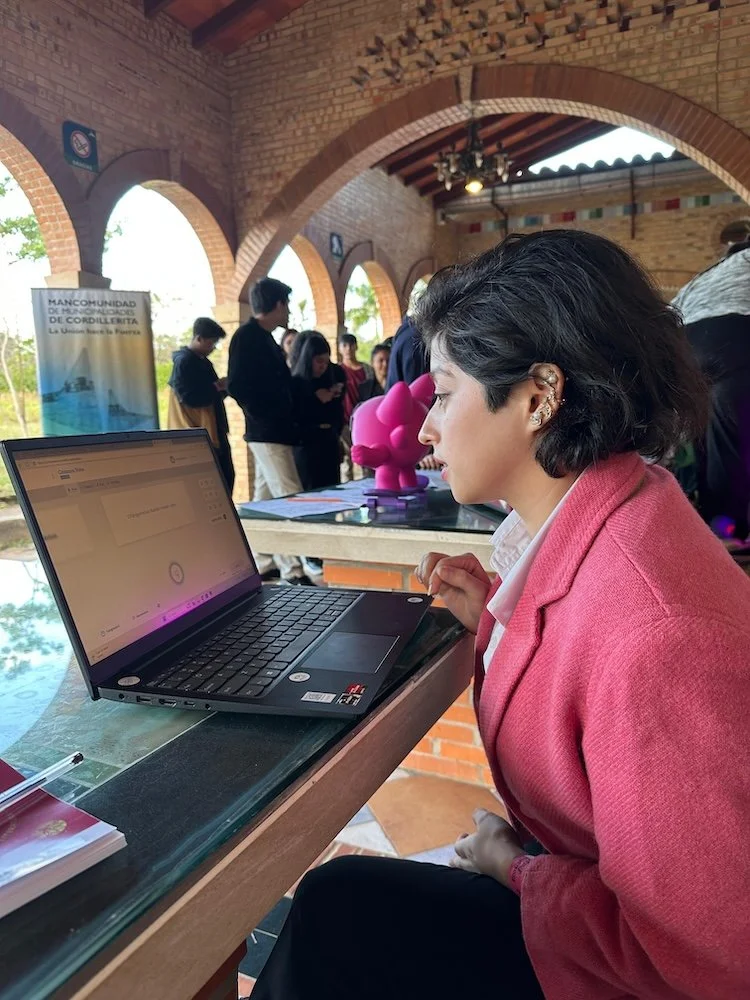

Audio validation in El Surti's pop-up AIKUAA station at the Roa Bastos Journalism Festival in Atyrá, 60km away from Asunción.

What’s next?

In the coming months, we’ll continue expanding the dataset, refining our validation processes, and deepening our connection with the communities that speak — and live — the language.

While civic participation through the mingas is already a powerful achievement aligned with El Surti’s mission and vision, we also hope that improving the public Guaraní dataset will strengthen both our editorial tools — for example, enhancing AI-powered transcription — and our community tools, such as improving the chatbot that manages subscriptions and responds to subscribers’ needs.

Our ultimate goal is to develop a replicable methodology that other media outlets can adopt to better serve oral-language audiences, contributing to a more inclusive and representative AI ecosystem in the Global South.

One of the community mingas in Arroyito.

AI that brings us together

We began this project deeply convinced that the most meaningful uses of AI aren’t for content generation, but for building real-world, person-to-person interactions that create deeper relationships between people and the media they support. And we’re starting to see that come true.

With AIkuaa, we're not just training machines — we’re creating spaces where people feel seen, heard, and part of something bigger.

Usually, these are state-level efforts, but we can’t afford the luxury to just expect this to happen on that level, because it might not happen at all. But with these initiatives, we’re trying to bring these issues into the conversation. And we’re just getting started.

———

This article is part of a series providing updates from 35 grantees on the JournalismAI Innovation Challenge, supported by the Google News Initiative. Click here to read other articles from our grantees.